Have you heard about the latest exciting European shenanigans?

There’s a new Copyright Directive on the way, and boy has it stirred up some passions. There’s an absolutely massive campaign going on to stop it, and air around Brussels is thick with accusations and recriminations.

Their arguments are impassioned, although anyone who takes the time to look for themselves will see that the changes proposed are not only relatively innocuous but also essential and positive.

The interesting thing is who the arguments are being made by, and how they’re being made.

The anti-copyright-directive gang are what we can now think of as the usual suspects, rehearsing the usual arguments.

For example, author and journalist Cory Doctorow has stated that planned changes are an ‘unthinkable outcome’ which pose ‘an extinction-level event for the Internet’.

Julia Reda’s pleas on behalf of her Pirate Party to #SaveTheInternet propose that Articles 11 and 13 should at the very least be radically amended, and scrapped entirely at the most.

Jimmy Wales and Tim Berners-Lee signed an open letter which states that Article 13 would take ‘an unprecedented step towards the transformation of the internet from an open platform for sharing and innovation, into a tool for the automated surveillance and control of its users’.

Even Stephen Fry has weighed in, calling the proposals ‘the EU’s looming internet catastrophe’. It is ‘not about protecting artists’ copyright’, he argues, but ‘about granting U.S. tech giants a license to dominate the internet’.

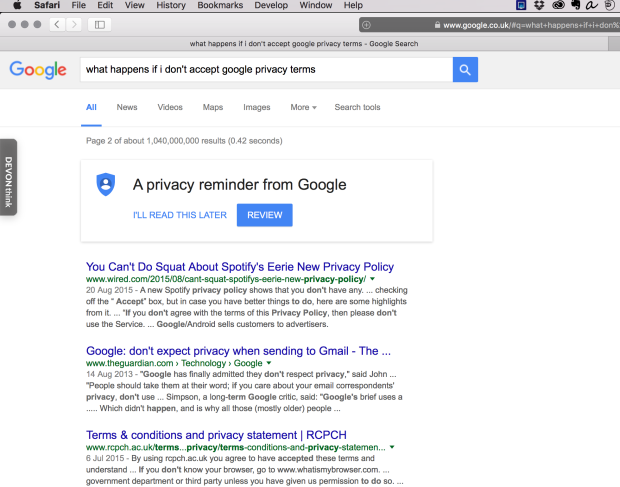

These arguments, some of them simplistic, some ridiculous, some bordering on hysterical, all have the same central theme. They confidently predict that these changes will break the internet, render masses of things illegal or impossible, stop people doing the normal things they want to do. Rather gloomy and doomy, rather extreme and actually – under scrutiny – rather wrong. We heard it before with SOPA and PIPA, and earlier this year when this directive had its first vote.

As well as impassioned arguments, the anti-directive campaigners have deployed technology to direct millions of emails and phone calls to EU legislators, purportedly from electors protesting the changes (although only a few hundred turned out to rallies around Europe in August).

The people leading this are, in great part, people who at one time were pioneers, who could have staked a decent claim to represent the future. These one-time pioneers now a little grey haired and grumpy, their objectivity twisted by time, their affiliations and paymasters, old obsessions and quirky perspectives.

The internet they dreamed of, and tried to make, was one which could easily change, which was in constant evolution, which produced greater and fairer opportunity and which gave everyone a voice and access to information and artistic endeavours.

The internet we have now is, though, quite a long way from that utopian idyll. The online economy is dominated by a small number of companies who capture nearly all of the money and data (whether you know it or not) and who share little of it. Access to all the information in the world isn’t breaking people out of ever-tighter and more easily manipulated filter bubbles – controlled by the same US tech giants that Stephen Fry fears so much.

Meanwhile, the right that everyone has to control their work – copyright – is worthless. Their work gets used without permission being sought, given or rewarded. So creators are going broke and creative companies are going bust.

That is the status quo which these anti-copyright people are trying to preserve.

Unable to paint an optimistic picture of a better, fairer Internet, they resort to predicting an Internet that is somehow even worse.

Ridiculous and untrue as their nightmare scenarios are, they’re also hardly earth shattering. “This will be the end of memes” they claim.

When weighed against the current undermining of copyright, creators’ loss of control over their own work and their inability to make a living from creativity, and the monopolisation of revenue by tax-avoiding mega-corporations, the loss of memes wouldn’t seem like a high price to pay – if it were true. But it’s not. As the Society of Authors points out, memes would be protected from copyright infringement as parody – and arguably other legal exceptions as well

Other opponents have given similarly feeble arguments, criticising the current status quo without offering productive solutions. Wyclef Jean, founding member of The Fugees, has campaigned for change without actually proposing any change. In an article for Politico, he expresses the need to ‘team up and make the music community work better for everyone’ without ‘demonizing and tearing down the internet and responsible service providers’.

“Links will be taxed”, they predict, absurdly. “The whole internet will be filtered by giant mega-corporations”. As if it isn’t already, but in any event, it won’t.

Some of these doom-sayers can be easily explained away. They’re not neutral, they have a vested interest in the status quo even if they try to hide it. Google spends huge sums funding organisations and individuals who can defend its interests while feigning independence.

Other activists are, dare i suggest it, just a bit past it. Stephen Fry, awash with cash, has no need for any Google largesse (and I’m sure receives none) and does not lack the intelligence to understand the arguments. Nevertheless, he still argues for the status quo. Perhaps having lived through the heady early days of the internet he just lacks the energy for any more change.

The internet as we know it now is still unevolved, primitive and brutal. It’s unfair and it farms its individual users as if they’re cash crops for the few.

We need to believe that it can change for the better. Restoring the rights of individuals is a key starting point for that.

Anyone who argues, fearfully, that change cannot be good and must be resisted is either being disingenuous or has simply stood by as time has rushed past them and find themselves now looking around and wishing it would stop.

Support the copyright directive, support the rights of individuals, support a fair internet which functions for all its participants.

Imagine it better, then make it happen.