Is free really a radical price or just radically irrational?

Some say content will become free as a matter of economic necessity. That as the cost of copies of content approaches zero, so will its price. That we are in the grip of an all-powerful economic principle which will sweep whole industries before it, and the fact that so much content is given away online proves their point.

I say that the cost of content, in pure economic terms, has always been zero. That the “pure” economics of physical goods, applied to intangible products like content, led to terrible outcomes the last time it was tried, leading to a change in the law to prevent it happening again. And that this law, now being widely ignored, is the answer both to the “content wants to be free” pseudo-academics and also the problem the content industry now faces.

Cost=value?

I am not an economist. I am not an academic. I didn’t study much of anything. So forgive me if I tempt fate by taking a mighty leap to address a – seemingly academic – point which has become trendy among certain prophets of the digital age who, presumably, hope their wisdom will become self-fulfilling.

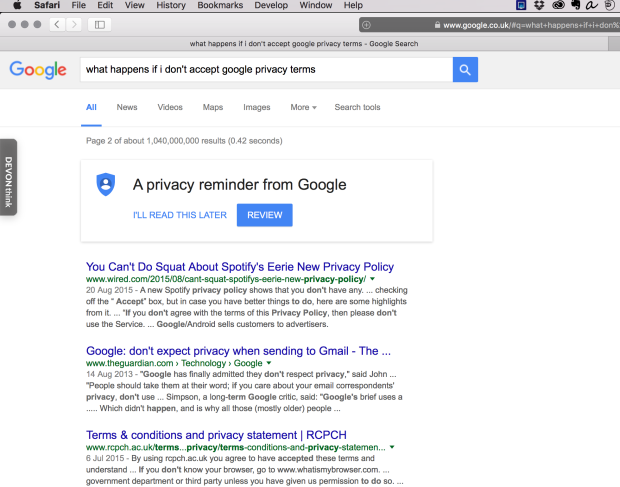

The academic point in question concerns the price for which content is sold online. More specifically, the point made by many that the rules of the internet radically change the economics of publishing, such that the aspiration to charge users for content is hopelessly unrealistic. Only dinosaurs think that way, we’re told: people who understand the internet also understand that giving things away is the key to reaching a lot of people, and reaching a lot of people is the key to making money.

So free, to quote the cover of Chris Anderson’s counter-intuitive but attention grabbing book “Free”, is “a radical price” which will define the future.

(An aside: I tried to get a copy of Free for, er free. It was available as a digital download for nothing at the time it was published. However now it’s not available free. The “hardcover” edition is available as a Kindle download for £12.15. The “paperback” edition – with a new, less embarrassing, strapline – is available for £5.45 in print but not at all on Kindle. So much for the radical economics of the internet).

Anyway, the argument goes something like this: making copies of digital things doesn’t cost anything. Economists tell us that in a perfect economy the price of something will tend towards its cost of production. For something which costs nothing to produce, like a digital copy, the price will tend towards zero. The fact that so much content is available for free is proof that the market is working well and the internet is fulfilling its potential. (Expand this argument to 400 pages and sell it and you too can be an internet guru as well as a rich author).

The sub-argument is that having so many consumers of your stuff gives you the chance to sell them other things, like concert tickets instead of CDs, or slightly better things, like CDs instead of downloads for your hardcore fans (or, like Chris Anderson, hardcover books, speaking engagements, consultancy and a day job editing an old media magazine as well as temporarily free downloads). So you can make money that way, in a way the content is a loss-leader for whatever else it is you have to sell. This is known as “Freemium” – you reward the people who care little for your stuff by giving them what they want for nothing, and punish those who really love it by charging them for consuming a lot of it.

Circular thinking

I think these arguments are a perfect illustration of what is wrong with internet thinking. So much of it is a post-rationalisation. It starts with a utopian picture of the internet the way the thinker would like it to be, idealised so that everything they care about is plentiful and – with the exception of whatever it is which makes them money – free. It progresses into the real world, via people and businesses simply behaving as if their utopian ideal were a reality (this is called, proudly, “a disruptive business model”), unencumbered by any old-world rules. It finishes with a seductive, intellectually feeble, post-rationalisation of the outcome whose main purpose is to justify itself and perpetuate the insular interests of those who profit most from the changes. An honest consideration of the broader picture almost never features and the interests of users and society as a whole, almost always claimed as the ultimate justification for whatever is being argued, are virtually never really considered.

So, back the economic argument for content being free (or, in some cases, for copyright no longer being relevant). The central point is that the cost of a digital copy is zero.

Cost has always been zero

My counterpoint is that the cost of copies of content has always been zero. When books first started being mass produced, the cost of the content, as opposed to the paper, ink, binding, distribution and so on, was always nothing. You used the same amount of ink however you arranged it on the paper. The words themselves made no difference to the cost. A CD costs the same (about 9p) to manufacture whether it contains a Lily Allen album or Microsoft Office but might be sold for anything from a few pounds to a few thousand pounds depending on what it contains.

It’s the content which creates the value. The bits, not the atoms, are the product whatever it looks like on the shelf of a shop.

So in my view, it’s pointless to consider the economics of content in terms of the manufacturing cost of copies because doing so not only defies everything we know about the content economy but also leads to perverse outcomes.

We�ve been here before…

There was a time when the “natural” economics were the only kind around. The world was about supply and demand, the materials which went into something more or less defined the whole. You could add up all the costs of something, add on whatever margin you thought you could get away with, and sell your product.

The thing which changed it was books. The advent of the printing press revolutionised the way in which knowledge could be shared and spread. For the first time mass production could make books affordable to the masses. Great things would happen.

However, the economic realities lagged behind the industrial surge forward. Although printing was indeed cheaper and easier than ever before, the main value of a book was the words on its pages rather than the pages themselves.

Bits and atoms 300 years ago

Unfortunately the laws of supply and demand didn’t recognise this. They only dealt in atoms, not bits. So the people who wrote the books, who created most of the value, tended to get a bit of a raw deal – however successful their book might be they rarely made much money. So not many books got written. The authors usually had better and more lucrative things to be doing.

So a law was written, the now infamous Statute of Anne, the first modern copyright law. Its aim was to ensure authors were properly rewarded for their work, to end the “ruination” of them and their families which too often had happened in the past. And it did this in a simple way – by giving them control over copies of their work. By recognising that the bits had a value beyond the atoms of the paper and ink, and putting in place a solution which would allow the value to be determined by the market.

And so, a book or CD which costs a few pence to produce is sold for a few pounds. JK Rowling is a billionaire. Hundreds of thousands of books are published every year, hundreds of TV channels flourish and thrive, countless movies are made every year and the creative economy supports 8% of the overall UK economy and over 2 million jobs. Even the printers, publishers and distributors of books, who would have seem to have got the raw end of the Statute of Anne, are still doing fine. Taking a smaller, fairer, slice of a much bigger pie, and thriving nonetheless.

All be recognising that the words, or the bits, have value separate from the paper they’re printed on, or the atoms.

Forward to the past

Fast-forward to the internet. Here we find ourselves in a situation a bit like the pre-copyright era. For a number of reasons, most of which are for another day, mass market publishing is only possible online for no charge. The only direct revenues available to publishers are from advertising, but they are competing for a smaller slice of an ever-diminishing advertising pie (I’ll come back to this point in another post as well). Success is about scale, quantity trumps quality.

So the people making money are those who pay the least for their content. The most money is made by the people who pay nothing (Google, overwhelmingly). The people who pay nothing, who benefit the most from content being free, are also the strongest advocates of content being free as a force of nature or of economic reality. They ignore, because it doesn’t matter to them, the actual reality that if the returns on the investment of time, money and creativity diminish so will the investment.

Free isn�t worth the paper it isn�t written on

To me the “free” idea is as worthless as it suggests. To my mind it’s simply wrong, and it destroys value for almost everyone except the person sitting at the tip of the pyramid.

Anyone who wants to be able to make a living from their creativity should be able to choose to do so, and choose their way of doing so, without the odds being so heavily stacked against them. I hope this is about to become a bit easier.