I’ve been hearing this phrase “the free flow of information” a lot lately. It’s been in the context of the “Publishers Right” and it is usually preceded by the phrase “will restrict”.

The heart of the concern seems to be the idea that if permission is needed before digital publications can be exploited by others, it could limit, for example, the ways in which those works can be indexed and discovered in search engines.

The argument seems to be that restricting access to “information”, imposing conditions on its use or treating some users, like automated machines, differently from others, like humans, is not just improper but sinister and shouldn’t be allowed.

Google are a leading voice in this argument, so lets have a look at how they work.

Google’s mission “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” is pretty much the ultimate expression of the ideals of free information advocates. For them to make something universally accessible it has to be completely unrestricted. But how unrestricted and accessible is Google itself?

You might not know it, but you can’t use Google without their permission and in return for a payment. If you’re a Google-like machine, you can’t access it at all. The universe of those who can access Google is rather less all-encompassing than their mission suggests.

Try this. Download a new web browser, install it, don’t copy across a any settings or cookies or anything. The go to Google – don’t log in.

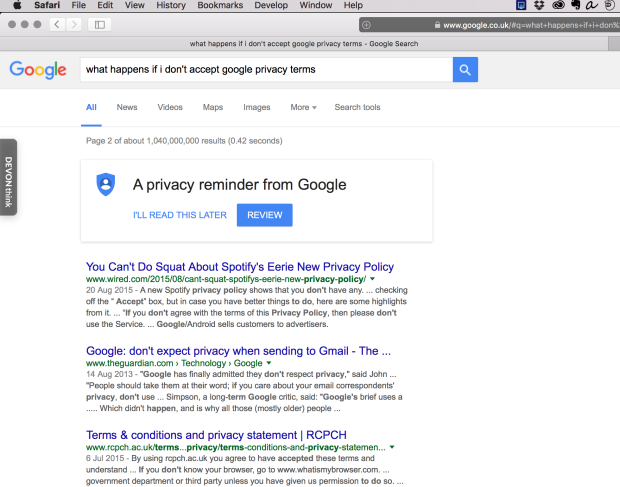

You’ll see something like this:

A little privacy reminder about Google’s (increasingly extensive) privacy policy sits at the top. If you click through you’ll be asked to click to show you accept the policy. Nice of them to go to effort to make sure you’re aware of it especially because it gives them pretty extensive rights to gather and exploit information about you.

This is how they pay for the free services they offer – they take something valuable from you in return and use it to make money for themselves. It’s a form of payment.

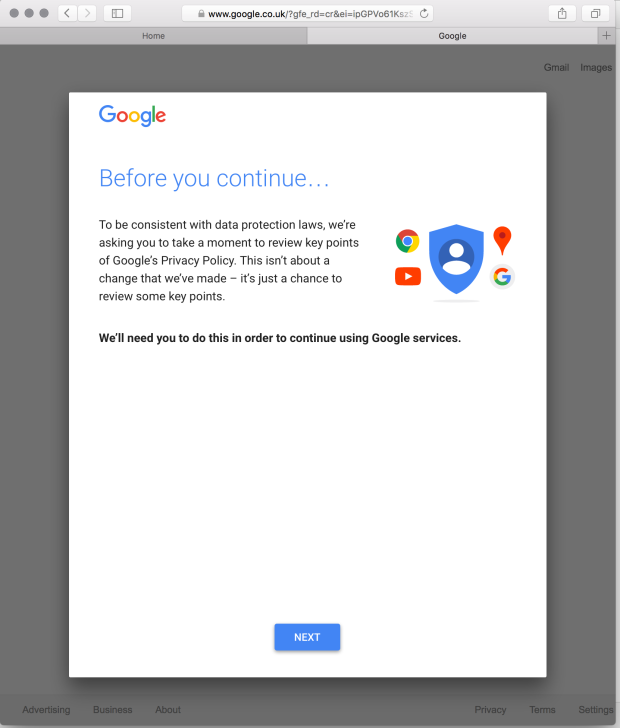

And if you don’t click to accept it, eventually you’ll see something like this:

You are actually not allowed to use Google until you have agreed explicitly to give them payment in the form of the data they want to gather and use.

So: using Google can only be done with their permission and in return for payment in the form of data.

There’s no technical reason for Google’s restrictions. They could offer a search service without gathering any data about users at all (and other services do). Their reason for these restrictions are obviously commercial: they need to make money and this i how they do it.

Whether or not you consider this to be reasonable (after all, every business needs to be able to make money), it doesn’t seem to sit very comfortably with their mission to make “all the world’s information… universally accessible”.

Nor, by the way does their blanket ban on “automated traffic” using their services, which includes “robot, computer program, automated service, or search scraper” traffic. They ban anyone who does what Google does from accessing the information which they have gathered from others using automated traffic. “Universal access” in Google’s world doesn’t apply to services like Google – it is a service for humans only.

Again, you might think this is reasonable, but contrasting it with their demand that their machine should be allowed to access other peoples services without restriction or permission is interesting.

Google insists that everyone – human and machine – needs their permission (and needs to pay their price) before accessing and using their service. But they oppose any law which might require Google to similarly obtain permission or pay a price when they access other peoples services.

It’s absurd that there should be such a strong lobby against such an obviously reasonable and uncontroversial thing at the Publishers Right.

Google is a company which vies to be the world’s largest, and which depends for its revenues on its ability to impose terms, restrictions and forms of payment on its users. It’s hypocritical of them to object to the idea that other companies should not be allowed to do the same.

The objections to the Publishers Right, and copyright more generally, are far too often the self-interest of mega-rich companies posing as the public interest. The credulity of politicians has, thankfully, reduced in recent years and they are more inclined to regard such lobbying sceptically.

There is no conflict between the need of media companies to have business models which allow them to stay in business and the “free flow” of information. There is no conflict between the desire to distinguish between human users and machine-based exploiters of their content.

For information to flow freely, those who create it need to be able to operate on a level playing field with those who exploit it, and need to be able to come to agreements with them about the terms on which they do so. To suggest otherwise, even in the most libertarian of language, is absurd.